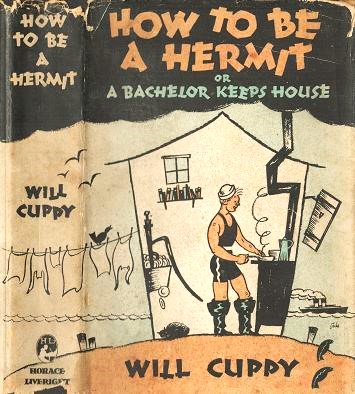

A long-standing cliché stereotypes satirists as dissatisfied loners, even misanthropes, with a dim view of the human condition. Few fit that suit better than William Jacob Cuppy, an embodiment of a loner who rose to fame with his first book, How to Be a Hermit. He truly lived the life as well, giving the oceanside shack he inhabited the name Tottering-on-the Brink. That was his favorite place on earth. Second place went to The Bronx Zoo. Three books of short pieces on animals constituted most of his lifetime publications. He would surely have found it fitting that he toiled obsessively for sixteen years on the book he considered his “masterwork” – similarly judged by almost everybody else – and it did not appear until a year after his death.

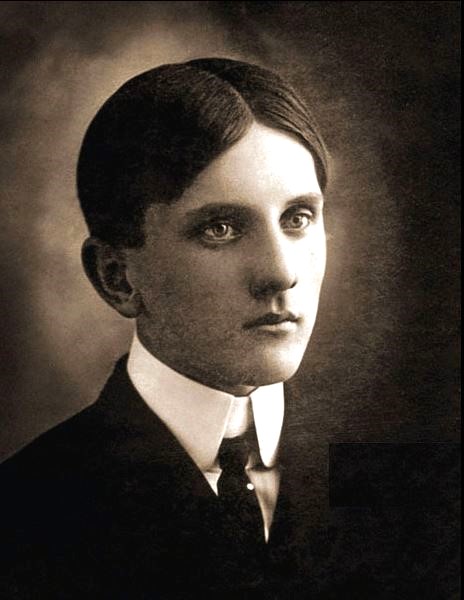

Cuppy put himself through the University of Chicago by freelancing for Chicago newspapers, quite a feat as he stayed there twelve years and only gave up halfway through his dissertation.

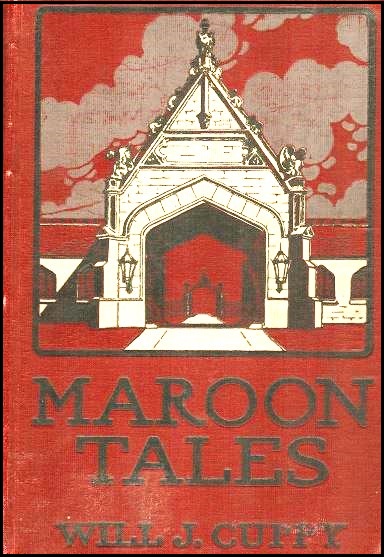

An early book of humorous stories about college life, Maroon Tales, appeared in 1910. Naturally, he didn’t like it. He wouldn’t publish another book for twenty years. Those are what we call high standards.

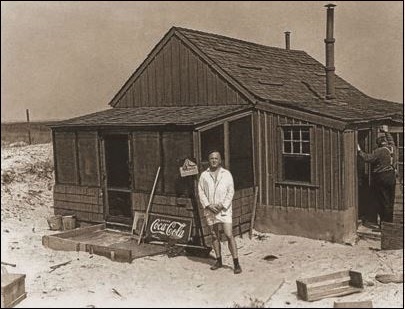

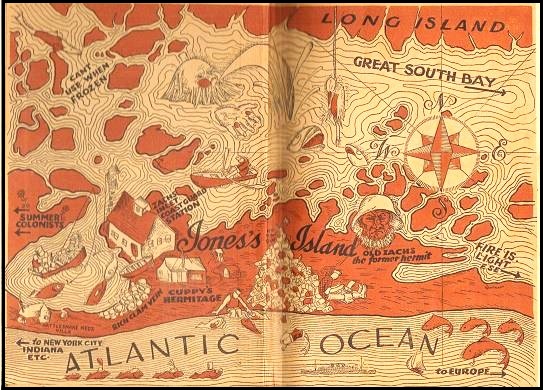

Cuppy moved to New York and kept writing incessantly, managing to make a less than living wage. Hence his move to a shack on the far fringes of Jones’s Island, off the coast of Long Island.

How to Be a Hermit was a loosely connected series of humor pieces that described both his struggle to survive (no road connected the island to land at the time) and the eccentric characters who shared the beach. He fit right in.

Published at the end of 1929, the book was a national success.

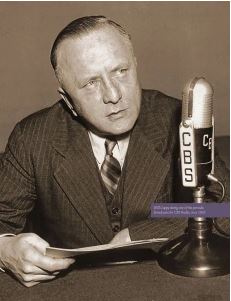

For a hermit, Cuppy knew how make friends, both with the cream of the literary world and others. The little spending money he needed was provided by reviews of mystery novels at two dollars a crack for the New York Herald Tribune. (Later expanded to a weekly column, his reviews ran to more than 4000 titles over the years. He would edit two books of mystery short stories.) Pre-merger, Burton Rascoe reigned over New York writing life as the literary editor of the Tribune. His assistant, Isabel Paterson, became Cuppy’s best friend. She had her own column and included bits of Cuppy whimsy regularly. Both practically adopted Cuppy and assisted his entry into the humor world of the 1920s, when it similarly reigned in New York. Her grandiloquent rave review of Cuppy got reprinted as the book’s back cover.

Being famous greases wheels in any era. Hermit shacks a few minutes from growing New York couldn’t be expected to withstand the expanding needs of the metropolis. Lord of infrastructure Robert Moses proposed roadways to connect the island with the mainland and create Jones Beach State Park. He swept the shacks away but Cuppy not only got special dispensation but a write-up in his autobiography. Who would have expected the almighty Moses to provide the best capsule description of Cuppy’s life?

He was a … writer of sorts. Every now and then Will journeyed reluctantly to the big town, sold his stuff to the slicks or pulps, slept after hours on the operating table of a kindly doctor in Greenwich Village, and then hurried home to his beans and sardine cans. He lived on handouts from the nearly Coast Guard gobs and from our engineers and for variety snatched some of the clams the gulls dropped on the spreading concrete. … In the race between progress on Jones Beach and Cuppy, we had to make an agonizing appraisal. We saved WIll. We made the right decision, but hermits must move a little further from town.

Despite the reprieve, Cuppy found living next to a public park intolerable and left, just about the time his book was being published. He found an apartment in Greenwich Village and didn’t leave it for two decades. Sometimes he took that literally, refusing to go outdoors and having his food delivered, all the while complaining about his neighbors.

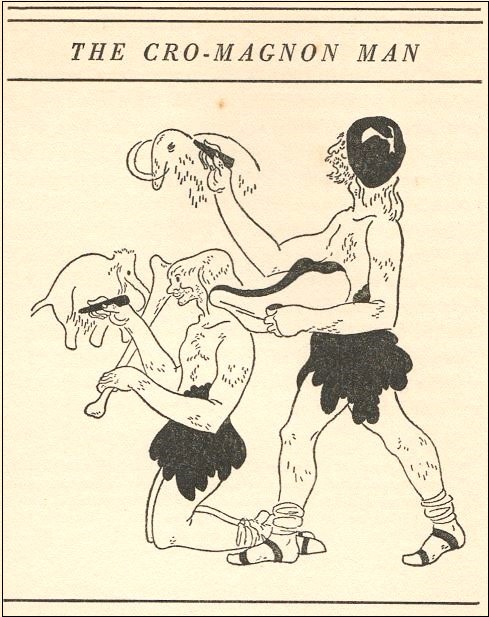

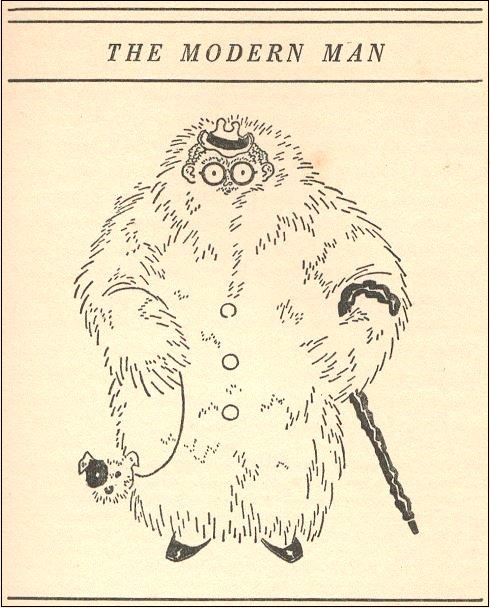

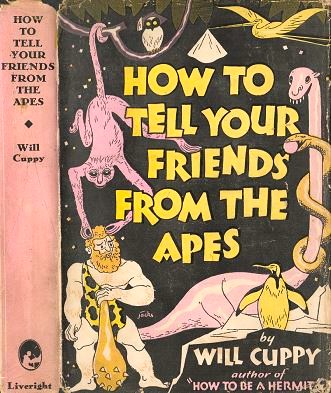

Despite having neuroses as roommates, Cuppy’s work now had a real audience. His name appeared regularly in magazines and collections of humor and he needed but two short years to publish his next book, How to Tell Your Friends from the Apes, which topped the reception of his first one. These short pieces on a menagerie of animals gave him a short-lived association with The New Yorker. He also placed the intro there, a series on the evolution of humanity from Java Man to Modern Man or Nervous Wreck. Book illustrations by somebody billed as “Jacks” were equally satiric.

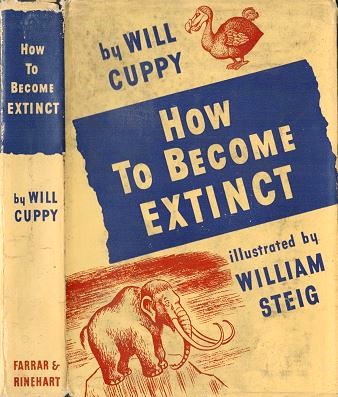

Cuppy’s bleak worldview couldn’t have improved when his next book, How to Become Extinct, was published just a couple of weeks before Pearl Harbor. The title was fatal, no matter that the volume consisted of more of his animal essays and extinction applied only to pterodactyls and dodos. Some of his articles were first published in a short-lived magazine called For Men Only, which, no matter what the covers implied, was a humor magazine.

This obscure, throwaway magazine is important only because it was edited by Fred J. Feldkamp, another in the long line of people who befriended Cuppy and who turned out to be perhaps the most important person in his life. Or certainly afterlife.

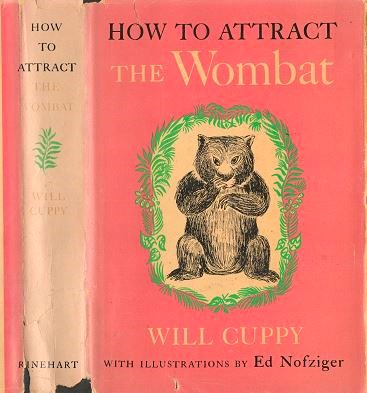

The last book Cuppy finished was yet another book of short animal pieces, How to Attract a Wombat, published for the Christmas buyer in December 1949. It received next to no attention, possibly because he had been forgotten after publishing little humor during the war and possibly because word had spread that Cuppy had committed suicide three months earlier. Years of illness and isolation had gotten to him, and a threat to evict him from the apartment he called home for 20 years was too much.

Yet his friends couldn’t and wouldn’t let him go. Feldkamp and his journalist wife Phyllis spent nights and weekends for a year going through the estimated 200,000 index cards he had stored in hundreds of boxes. These were filled with barely decipherable hand-scrawled notes and fragments someday to be consolidated into his next book. The Feldkamps acted as humor paleontologists digging up the bones of multiple mythical beasts that they consolidated beautifully into a museum of finished works that told a complete history of the world. Two dozen biographies of famous names comprised The Decline and Fall of Practically Everybody, the laughs multiplied by Cuppy’s specialty, multitudinous footnotes. Forgotten Humorist Richard Armour paid close attention and created a bestselling career of similar books. (To be fair, they were both copying W. C. Sellers and R. J. Yeatman’s classic 1066 and All That.)

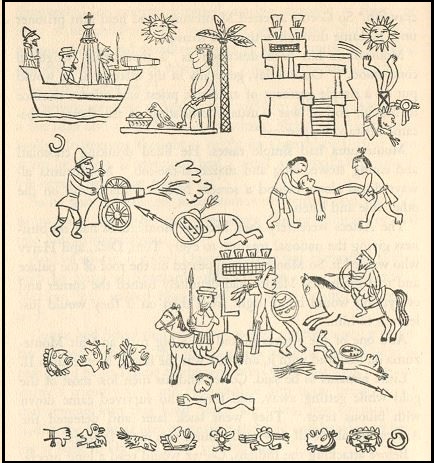

William Steig (yes, Shrek Steig, then better known as a New Yorker cartoonist) supplied 55 illustrations. To be honest, I thought “Jacks” were funnier but a legend sells more books. Here’s one of his best, from the chapter on Montezuma.

Just like Forgotten Humorist Oliver Herford, Cuppy’s social satire came with a real sting. One of my all-time favorite lines comes from the chapter on Miles Standish.

“They [the Pilgrims] believed in freedom of thought for themselves and for all other people who believed exactly as they did.”

The book received at least 20 times the number of reviews as Wombat, most gleefully positive. Walter Winchell, then the most popular newspaper columnist in the country, reprinted the entire chapter on Columbus in his column. With permission but without the footnotes, leaving a treat for book buyers. Of which there were many. The book stayed on the Los Angeles Daily News bestsellers list for more than six months, just behind monsters like Kon-Tiki. Eventually it went into 18 hardback printings, 10 foreign editions, and oodles of paperback editions. I have an 18th printing of a 1984 trade paperback, issued with a new afterword detailing Cuppy’s life.

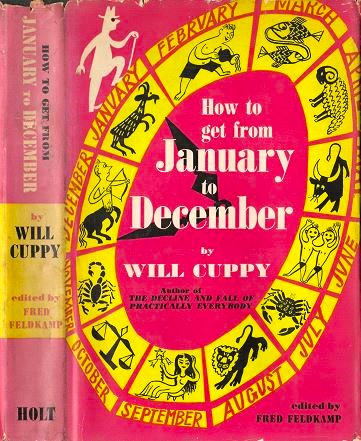

The public demanded more Cuppy. The Feldkamps went back to the index cards. In a marathon of effort, they pulled 366 short tidbits and arranged them into a daily almanac titled, of course, How to Get from January to December. Anticipation ran high with newspapers teasing readers with illustrations before they ran reviews.

Reviews were positive, but the book didn’t make bestsellers lists. With no more material forthcoming, Cuppy faded away, although a few acolytes kept his name alive by reprinting him over and over. I encourage people to buy one. Copies of DeclIne and Fall are available for practically nothing. His epic putdowns of history’s legends are as lasting as the pyramids.

Bibliography of Humorous Works

- 1929 – How to Be a Hermit

- 1931 – How to Tell Your Friends from the Apes (pictures by Jacks)

- 1941 – How to Become Extinct (illustrated by William Steig)

- 1949 – How to Attract the Wombat (illustrated by Ed Nofziger)

- 1950 – The Decline and Fall of Practically Everybody (edited by Fred Feldkamp; illustrated by William Steig)

- 1951 – How to Get from January to December (edited by Fred Feldkamp; drawings by John Ruge)

You must be logged in to post a comment.