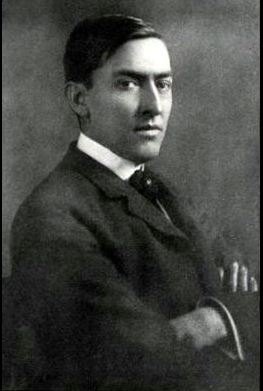

George Ade grew rich enough from his writing to buy himself a county. So the story goes. He really did get rich: he’s said to be the first comic millionaire. He did have a full career as a newspaperman, columnist, essayist, short story writer, actor, and playwright, and then went home to Indiana and started buying up land. A whole county? Well, no. But imagine being so rich that such a rumor seemed plausible.

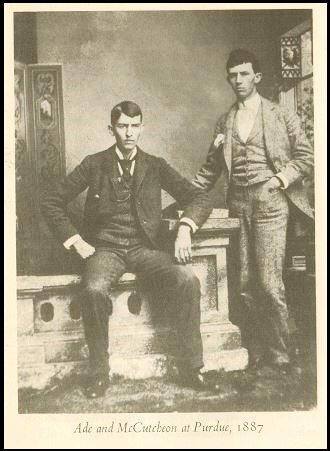

Born in Kentland, Indiana, the heartland of the heartland, Ade did exactly what so many other bright, book-loving boys did. He gave college a try, moving the 40 miles to then brand new Purdue University in West Lafayette. Not interested in the technical careers the college specialized in, Ade threw off his degree to descend into employment that would allow him to write, becoming a journalist in Lafayette. The Call paid him six dollars a week, some of that in meal tickets.

To make money in the newspaper game, prospects either had to have fantastic ability as an investigative reporter or have a voice, a style, a skill akin to that of chef who takes ordinary ingredients and and combines them in new and palate-thrilling ways. Editors made their own careers by spotting the one young man (never a woman) whose prose demanded to be run as a regular column.

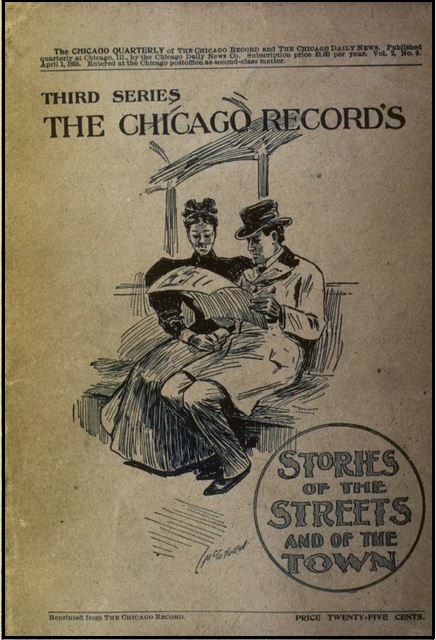

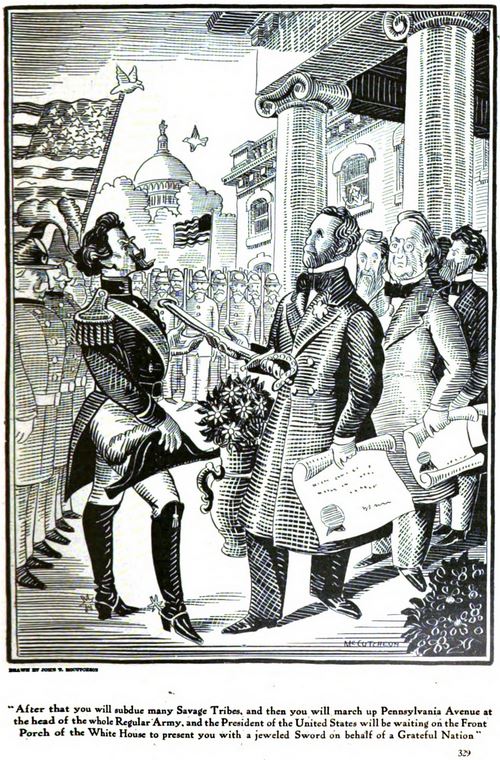

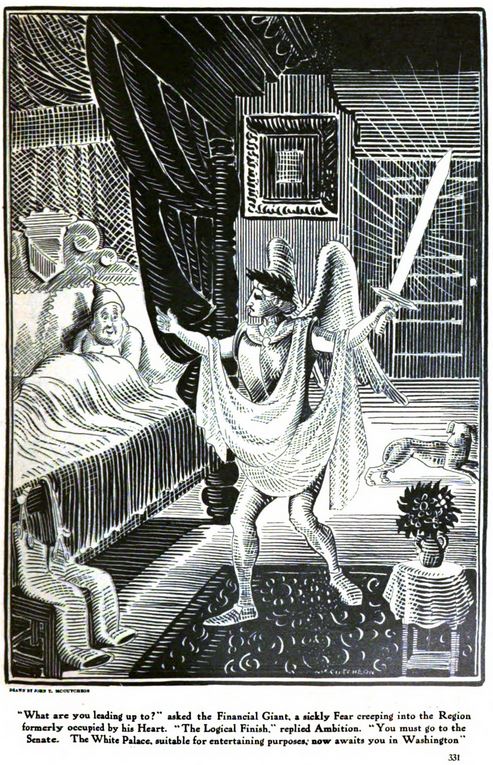

Ade got spotted immediately. A daily column, “Stories of the Streets and of the Town,” illustrated by college chum and lifelong friend John T. McCutcheon until 1897, ran daily and would be collected into eight twenty-five cent paperback books by the end of the century.

One glitch. The column was run anonymously. After ten years, the now extremely popular column was paying him all of sixty dollars a week. Great money for 1900 but far from a millionaire’s wages. In addition, Ade was bored by the repetition involved in a daily column.

One morning, I sat at the desk and gazed at the empty soft paper, and realized the necessity of concocting something different. The changes had been rung through weary months and years on blank verse, catechism, rhyme, broken prose, the drama form of dialogue, and staccato paragraphs.

Why not a fable for a change? and instead of slavishly copying Æsop and La Fontaine, why not retain the archaic form and the stilted manner of composition and, for purposes of novelty, permit the language to be “fly,” modern, undignified, quite-up-to-the-moment?

from Our American Humorists, by Thomas L. Masson

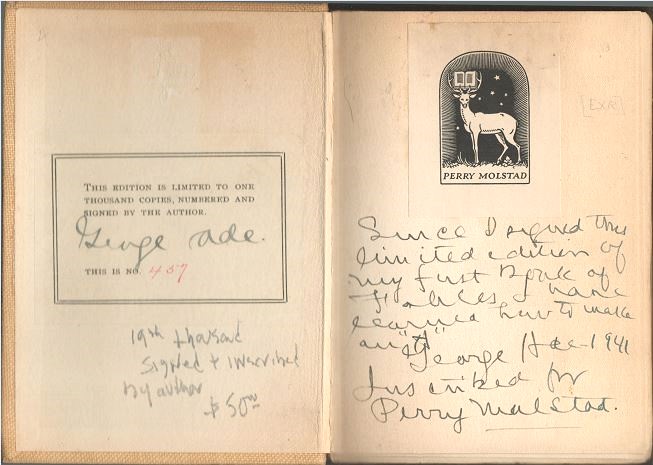

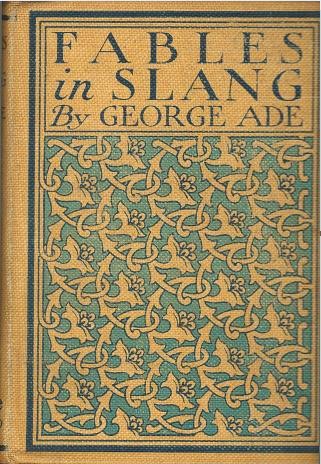

Never tempt the fates. After he got that first one out of his system, he didn’t give them another thought until almost a year later. This time they would become a sensation. In a very short time he would be trapped in Fables. At first he couldn’t believe his luck; Fables in Slang would sell an astounding 69,000 copies in 1900 alone. By June, the 19th thousand was issued as a signed and numbered collectible in a mere thousand-copy edition.

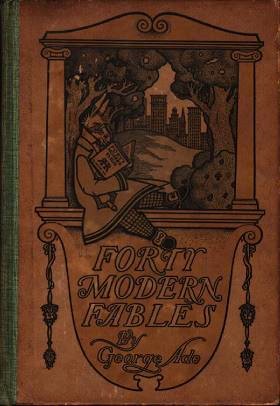

As a daily columnist he had a huge backlog of product to disseminate. The second book, More Fables, also came out in 1900. I had the luck to pick up a copy not only signed by Ade but also signed and with a fabulous pen and ink drawing by illustrator Clyde J. Newman. A third, even larger, collection, Forty Modern Fables, also appeared in 1900. (To be precise and pedantic, Fables in Slang was released in December 1899. but the bulk of sales took place the next year.)

Ade’s Fables always took a kick at current morality or customs or standards. They were rude, impudent, and revealing of the shabbiness of society’s formal dress. Some satire is timely, some is timeless, and a rare few are both. Ade’s barbs are mostly thrown against urban figures he regularly encountered on the bustling streets of Chicago, so ordinary that everyone recognized a next-door neighbor in them although nobody but Ade thought to pinpoint their foibles in print. He was a quintessentially urban humorist, truly “fly,” among the first of a new breed. Gone was the dialect humor that pervaded the works of 19th century humorists like Josh Billings, Joel Chandler Harris, Frances M. Whicher, and Petroleum V. Nasby and Artemus Ward, the working names of Charles Farrar Browne and David Ross Locke, known collectively as the cracker barrel humorists. Even Ade’s great contemporary Chicago humorist, Finley Peter Dunne, whose Mr. Dooley sat always in a Chicago bar and cracked great aphorisms about national politics, wrote in Irish immigrant dialect.

Ade’s sad sack characters never reached those heights. Only the barbs he hurled against them last through the century, and take but a slight twist of the wrist to apply to their descendants of the 21st century. Prefiguring the era of Instagram, Ade gives us a woman who brightens her appearance with makeup in order to step in front of every camera she sees, but “when she showed up on the Level, she looked like a Street just before they put on the asphalt.” Talk radio seems to be patterned on the Preacher who realizes that to not bore his petitioners he need only spark the sermons with meaningless profundities: “Perceiving that they would stand for anything, the Preacher knew what to to do after that.” And the matter of certain billionaires dotting their formal loan applications with “don’t believe anything” clauses is presaged by the man who said that “when he wanted something really Fresh and Original in the Line of Fiction, he read the Prospectus of a Mining Corporation.”

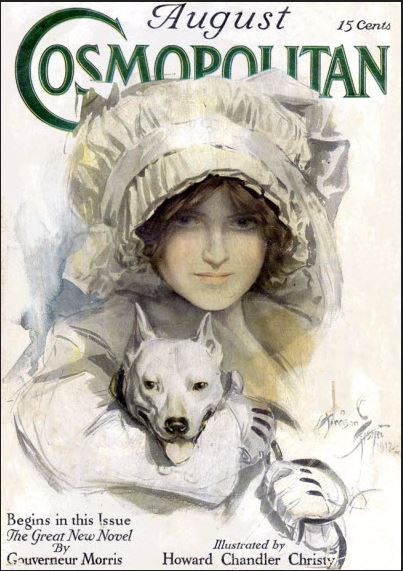

The wild success of the book brought offers for syndication. Soon Ade was making $1000 per week while needing to write only one Fable instead of the six for his daily column. “[T]he whole world seemed to be slapping me in the face with twenty-dollar bills.” Over the next thirty years he would write 500 fables, and about half would be reprinted into eleven collections. In 1912, he found an even easier gig: one Fable per month for Cosmopolitan Magazine, a major slick and conservative publication; no one then could conceive of Helen Gurley Brown taking it over a quick fifty years later.

Thanks to Google those issues are now digitized, and the content has gone into the public domain. Here’s the return of George Ade with new Fables in the August 1912 issue, illustrated, of course, by John T. McCutcheon.

A mere thousand dollars a week doesn’t make one a millionaire, even in 1900 dollars. However, being relieved of five-sixths of his weekly efforts left Ade with abundant time to toy with other fields that weren’t as repetitious.

Ade left Chicago for New York, the country’s center of theater, even more then than now. With one hand he churned out Fables and with the other from 1902 through 1910 he wrote nearly a dozen plays, light operas, and musical comedies. Just as Andrew Lloyd Webber made a billion dollars from musical theater, Ade made his big money from his stage work. Forgotten today as they might be, in the early 20th century plays dwarfed his Fables in the number of twenty-dollar bills thrown at his face. Ade earned something like $5000 per week at his peak and got dubbed The Baron of Broadway. Well, a biographer titled a chapter that way, but that’s still pretty good. I’d take it.

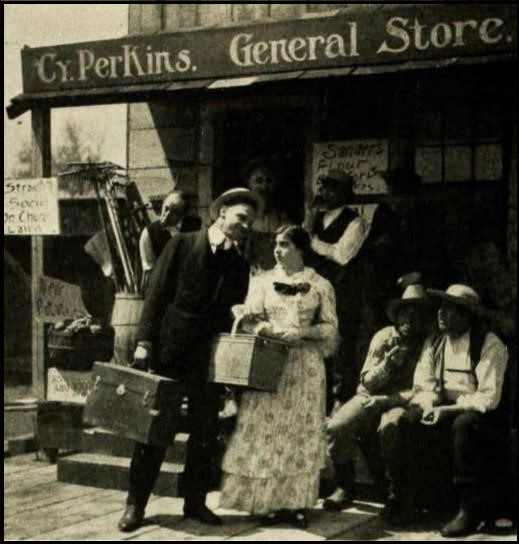

To go along with the publication of his eighth volume of Fables, Ade went to Hollywood and started making his Fables into short films, directing the first seven himself in 1914. A jaw-dropping 82 more followed though 1917, featuring such silent stars as Wallace Beery and Ben Turpin.

And then he became even more successful. A marketable play had a life after the original run. Ade’s works would be brought to the stage by local companies for decades, which kept the money rolling in. When talkies arrived, producers looked to New York for material to be made into movies (sometimes to be turned into musicals if they hadn’t been birthed that way).

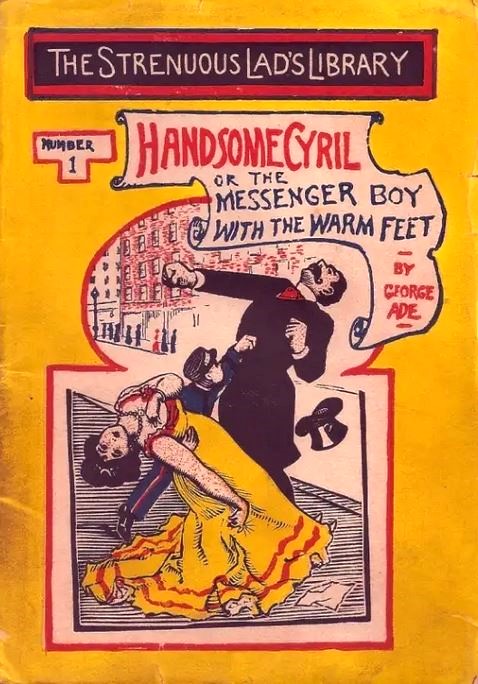

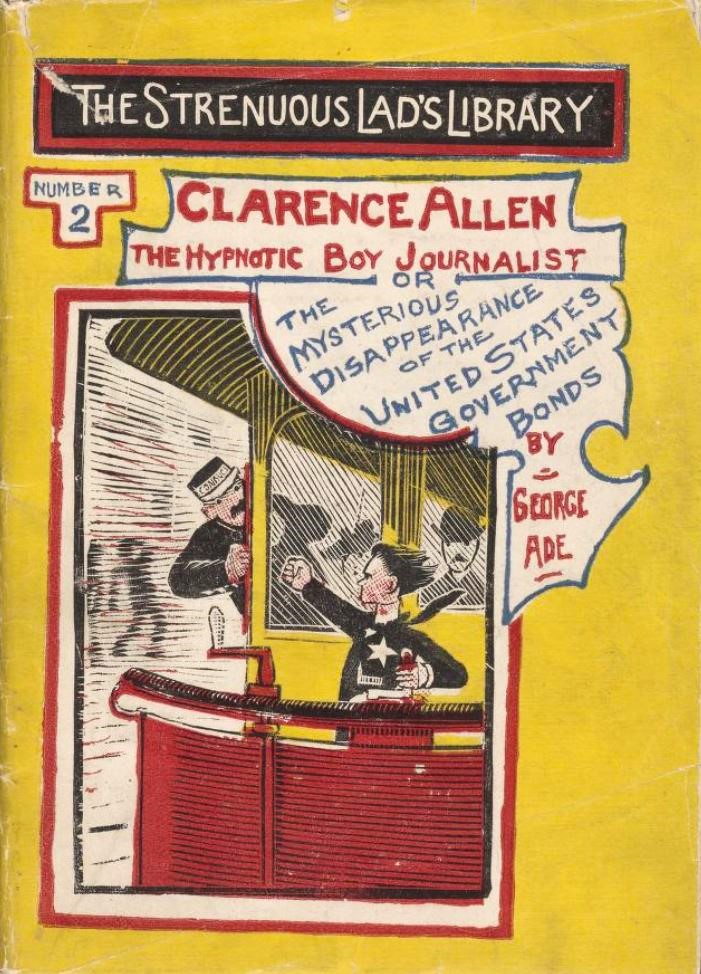

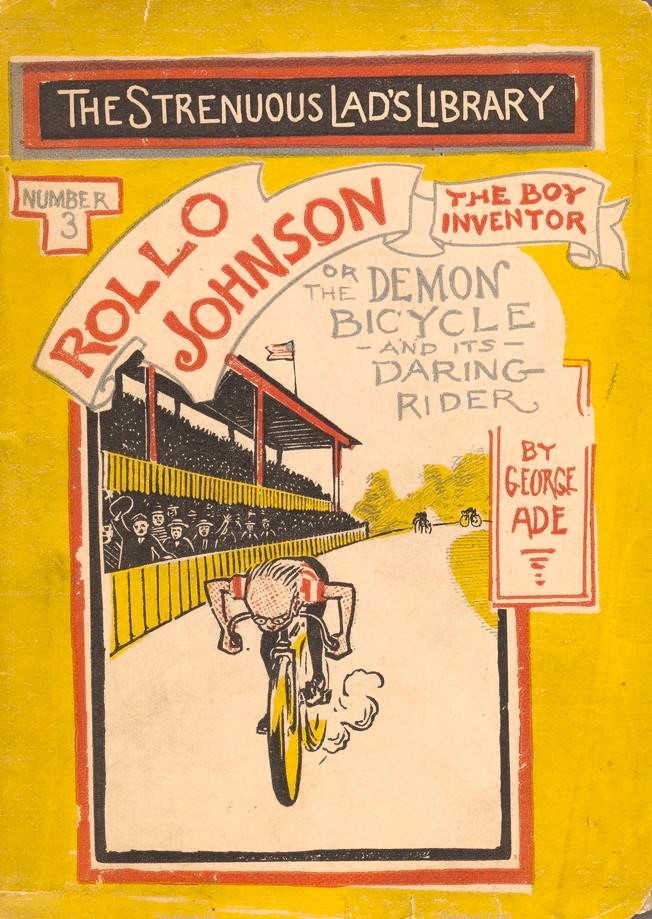

Out in Hollywood, the studios worked full-time trying to keep up with him. IMDb.com credits him with 34 productions beyond his short fables, many of them full-length movies made from his plays, spanning the era from silents to talkies. Or made from his novels. I haven’t yet had time to mention his novels, and his short-story collections, and his nostalgia fests about Indiana, and his series of boy’s books called The Strenuous Lad’s Library. Seriously. Or perhaps Comically. (They were not meant to mock the genre but they dated so badly and so rapidly that twenty-five years later he would spoof himself with a collection of stories, Bang! Bang!, caricaturing the boy’s books of the early century.) Most of the Forgotten Humorists chronicled here were almost unimaginably prolific.

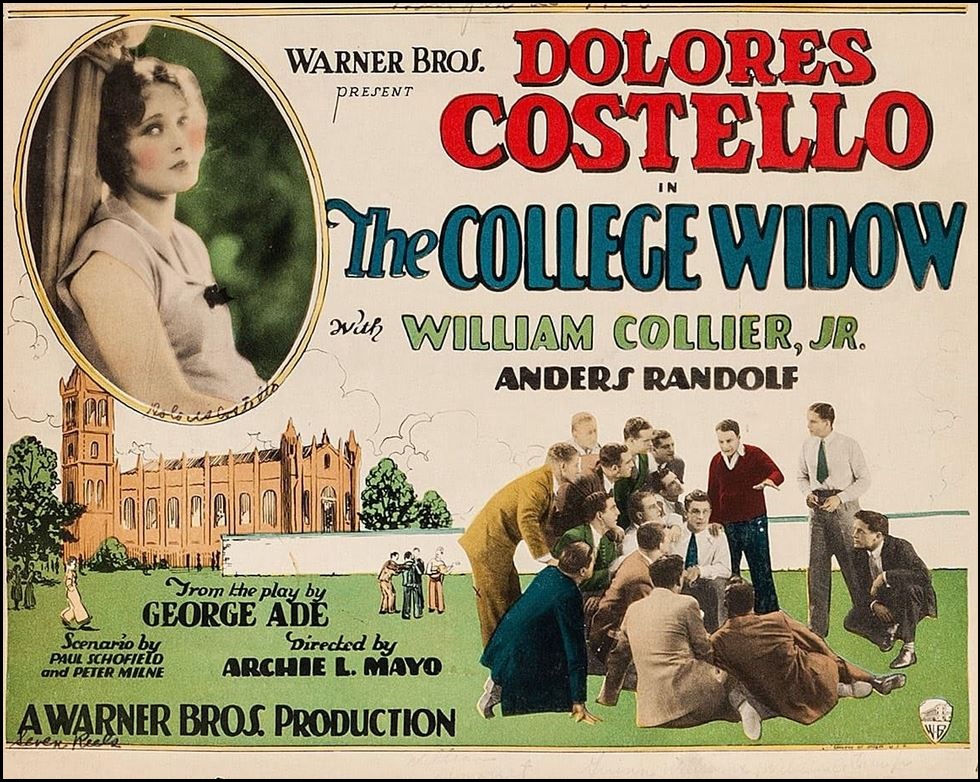

His most successful work rivaled the popularity of anything in the early days of sound film-making. Back in that ferociously busy play-writing decade, Ade turned out a risque little number called “The College Widow.” It opened in Washington D.C. in September 1904, where the Evening Star explained that a college widow “is a charming young person who knows more of the world in a minute than the entire sophomore class.” Royalties for the play are estimated to have reached two million equally delectable dollars over the years.

Aside: some sources credit Ade with inventing the term. Nonsense. I can trace it back to an anonymous story in the March 1856 issue of Harper’s magazine. Falling in love with a college widow was an experience every college boy longed for in the half century before Ade became about the ten millionth to use the term.

Despite its earlier ubiquity, nobody exploited the concept better than Ade. The play became a silent film in 1915 and again in 1927, starring Dolores Costello. A summary of the 1927 movie reads, “Following another instance of the perennial defeat of the Atwater College football team, President Witherspoon is told that unless better athletes can be induced to come to Atwater, he will be asked to resign.”

The Marx Brothers never did well with silence: even Harpo was noted for noises. They leveled audiences with a barrage of words starting in 1929; their fifth film earned them the cover of the August 12, 1932 issue of Time magazine. Horse Feathers placed the Brothers in Huxley College, with its President, Groucho, desperate to bring in ringers as football players to save the school. Matters are complicated by all four brothers – yes, including, and especially, Zeppo – in desperate pursuit of lovely Thelma Todd, the college widow.

Remember that date of 1932. Despite all the adulation given to the great S. J. Perelman for his work on this movie, the evidence is conclusive that he (or maybe one of the many other writers who worked on the film) stole its bones from The College Widow. The lines and business given to the Brothers are of course unmatchable, but unquestionably Thelma Todd is a relative of Dolores Costello.

And of Joan Bennett. Just to give an idea of how Hollywood worked in the early days, The College Widow had already been adapted as a Joe E. Brown feature, Maybe It’s Love, in 1930, two years before the Marxes’ version, featuring Miss Bennett as a more youthful widow, although she is called upon to flirt with the entire football team. (Shades of Clara Bow!) Then the plot was twisted to hide its forebears with a water-logged crew team in Boston in the 1935 girl-heavy feature Freshman Love. Not yet finished with plot-theft, the theme was sanitized for lovable Penny SIngleton, playing a teenager at the age of 30, wooing her basketball boyfriend in 1938’s Campus Cinderella. That’s five tighter or looser adaptations in just over ten years.

With all that, Ade was essentially forgotten within his lifetime. Dorothy Ritter Russo’s massive and unbelievably detailed Bibliography of Ade, published by the Indiana Historical Society in 1947, reveals that mentions of Ade in magazines and books virtually ceased after the mid-thirties when he retired back to Indiana (except for obituaries in 1944). A few acolytes remained. The Holiday Press of Chicago released a limited-edited, slipcased volume titled Notes and Reminiscences: George Ade/John T. McCutcheon in 1940.

Jean Shepherd edited and introduced a collection of Ade’s pieces in 1960. Terence Tobin edited his letters in 1973. Then quiet. I can’t find anything major in the over fifty years since, except entries in historical accounts of humorists.

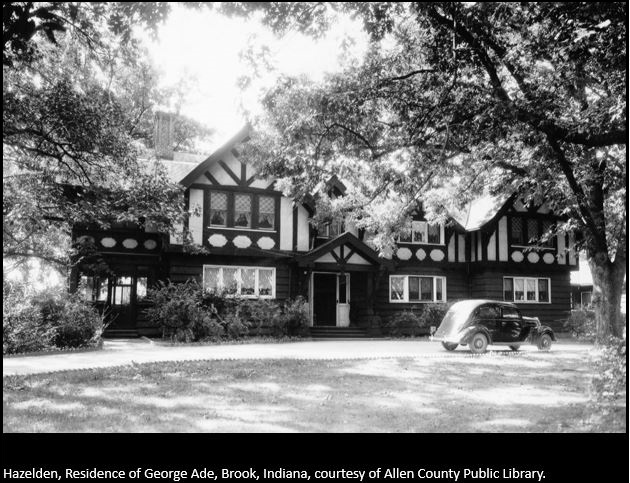

Ade may have cared about this fade from extreme accolades to an extent, probably while rolling in his money bin. The early money was enough to build a 14-room house, Hazelden, an hour east of Kentland. As he spent more of his time there, he added the usual amenities, like a swimming pool, greenhouse, and barn. Oh, and a golf course and country club. I’m about to drop in a fact that seems unbelievable for a mere comedian. Hazelden was the site where in 1908 William Howard Taft started his national tour to campaign for the presidency, speechifying to thousands of farmers. (It’s not where he announced his candidacy, as the Wikipedia page for George Ade House has it. The Republican Convention had named him two months earlier.) The house was put on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976, although funding for upkeep has been hard to raise.

Forgotten… except in heartland of Indiana. The George Ade Memorial Health Care Center, now a skilled nursing facility that replaced a hospital, lies on the Hazelden Manor grounds (which covered 2400 acres, almost three times the size of New York’s Central Park). A historic marker was set up to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of Taft’s big moment. (A little late, not appearing until 2009.) And the Hazelden Estate may finally be restored as the center of a complex of tributes to Ade: The George Ade Museum, The Gardens, The Carriage House, and The Newton County Visitors Center. In the heart of the heartland, Ade’s version of America will always live.

Bibliography of Humorous Works

Fables

- 1900 – Fables in Slang (Illustrated by Clyde J. Newman)

- 1900 – More Fables (Illustrated by Clyde J. Newman)

- 1901 – Forty Modern Fables

- 1902 – The Girl Proposition (illustrated by John T. McCutcheon, Frank Holme, Carl Werntz, and Clyde J. Newman)

- 1903 – People You Know (illustrated by John T. McCutcheon and others)

- 1904 – Breaking Into Society (multiple illustrators, not credited)

- 1904 – True Bills (multiple illustrators, not credited)

- 1912 – Knocking the Neighbors (illustrated by Albert Leverin)

- 1914 – Ade’s Fables (illustrated by John T. McCutcheon)

- 1920 – Hand-Made Fables (illustrated by John T. McCutcheon)

Other Humorous Works

- 1903 – In Babel

- 1906 – In Pastures New (illustrations by Albert Leverin, not credited)

- 1922 – Single-Blessedness and Other Observations

- 1928 – Bang! Bang! (illustrated by John T. McCutcheon)

- 1931 – The Old-Time Saloon (multiple illustrators, not credited)

You must be logged in to post a comment.